Rohan Kundargi Wants You (Yes, YOU) To Help Him Build A Stronger Community

By Kate Stringer

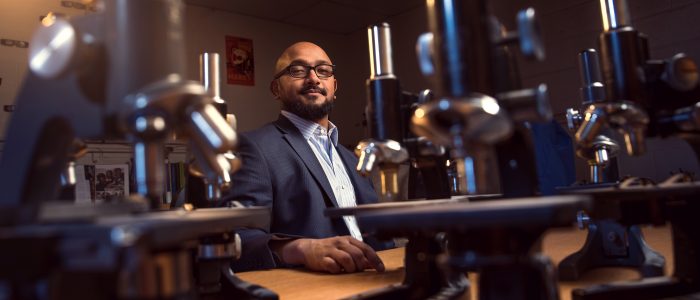

“I’m really passionate about what I do, but I also get really emotional about it.” Rohan Kundargi warns me as we sit down to discuss his new role as K-12 Community Outreach Administrator at MIT’s Office of Government & Community Relations. He needn’t have worried—what was portrayed as histrionic ardor for subjects like STEM learning, education reform, and public service actually comes across as warm, effusive enthusiasm, powered by deeply held convictions. In a broad-ranging conversation early last December, we discussed everything from erasing barriers between high school and college to the importance of reciprocity in institutional relationships, to the differences between Western Washington (what everyone thinks the state looks like—Seattle) and Eastern Washington (“basically Idaho”).

Joining the Community and Government Relations team in mid-September of 2018, Kundargi sees his role as a natural extension of his previous job at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, where he served for two years as Science Coordinator, a position created to bring Gonzaga’s K-12 STEM resources into the service of the local community. Though he speaks with great affection for his time in Washington, Kundargi is thrilled to be back on the East Coast and to tackle the challenges presented by his new role. He admits that the intensity at the Institute can be a little daunting, “I’m still getting used to the MIT-ness of everything,” but recognizes that it is uniquely placed to effect change in the educational landscape: “MIT is a role model for other universities… I would like to think that [if we start something], other universities will follow.” He’s also aware that his new home base offers a wealth of opportunities that are unique to this area. With the outsized number of universities based in Greater Boston, it’s easy to find people who share a commitment to and enthusiasm for effecting positive change in U.S. schools. It’s a privileged position to be in, which Kundargi says he didn’t realize until he left the area right after graduate school.

For Kundargi, who received his Ph.D. in Earth Science from Boston University in 2016, the move to MIT could be considered a homecoming on many levels. His fiancée is from the area and they had hoped to move to either Massachusetts or California (where Kundargi grew up) to be near family. But the Greater Boston area could also be considered his vocational birthplace. It was while completing his degree across the river that he first discovered a passion for pre-college STEM education. Struggling with organizational changes in his Ph.D. program, he found teaching provided a way to fund his studies. A National Science Foundation program called the GK-12 STEM Fellows offered to pay for his final year of graduate school in exchange for a year of co-teaching a 7th grade class at Broad Meadows Middle School in Quincy. Within a month, he says, he realized that “the program was giving [him] a reason to get up in the morning.”

Broad Meadows featured a diverse student body, including immigrants, refugees, students from the local housing projects as well as the children of the South Shore’s wealthiest families. In addition to the excitement of hands-on teaching, the experience gave Kundargi a renewed appreciation for his role as a racial minority working to effect change in the K-12 STEM landscape. “I’m a brown-skinned person,” he begins, “and I found that [my] being there, teaching climate science to 7th [graders]… there was a group of students who reacted to me in a positive manner that they didn’t react to other teachers, purely because I looked like them.” It reminded him that representative education—and representative educators—are a major part of changing and strengthening the fabric of the American educational system.

With these new experiences fresh in mind, he applied to STEM education-related jobs all across the country, landing at Gonzaga University, where he took on a role that gave him the freedom and autonomy to develop and create new K-12 opportunities as he saw fit. “Basically, I was treated like a postdoc,” he comments, noting that the freedom to experiment was a crucial part of his growth as he tested out his new career in education. He spent the next two years taking established science outreach programs at Gonzaga, growing them and getting them into more schools, working on all different program elements including logistics, curriculum development, recruitment of students and teachers, and of course, a whole lot of grant-writing. He also spent time working with local companies and government. “[Gonzaga] didn’t really have an existing relationship with the local school [systems], so I just built one because that needed to happen… I literally showed up at local schools to see department heads and said, ‘I exist’ until they’d talk to me and we’d build something.”

It’s an approach Kundargi hopes to bring to his new role, where his primary mission is to make MIT a second home to Cambridge K-12 students and teachers. “I very much believe that universities have a place in their local K-12 systems,” he comments. “I hate when people say ‘K-12’ and ‘higher education.’ We should be referring to it as K-16, K-20, because education doesn’t stop at high school, all the college students come from somewhere. It should be a kind of spectrum where you have undergraduates working with elementary school students, and elementary school students should feel extremely comfortable in a college setting.” As opposed to the all-too-common dread of what comes after high school, Kundargi believes that students should always feel like college is an accessible option, “a natural and simple choice, a continuation of their education as it’s always happened.”

The “K-16” outlook, Kundargi believes, may be an important part of closing opportunity gaps, beginning with those in our own backyard. He notes that despite the image of a newly affluent, up-and-coming tech hub, many in the Cambridge Port area are still among the lowest-income residents in Eastern Massachusetts and feel increasingly left out of what is perceived as the rarefied air of Kendall Square. “There are student groups I’ve talked to across the Port, who will say ‘You know, MIT’s not for me, I don’t belong there.’” For Kundargi, de-mystifying MIT is the first step toward breaking down barriers, and it’s as simple as bringing people on campus, making them feel as though our space is a just another part of the Cambridge landscape. He admits that while the Institute should, in his view, be open to the community, enrollment at MIT is not for everybody. But feeling comfortable on this campus means students can feel at home on any campus: “Maybe not every student should go to MIT, but every student should feel like they can go to college.”

It’s an ambitious goal, and Kundargi knows it. And more to the point, it will take time. But he’s in for the long haul: “I’m planning on being in this job for years. Both my bosses have been here for over 25 years. They’re people who have developed [key] relationships, and now use those relationships for good. So what I’m hoping is that in the years moving forward, [we’ll] just kind of have this synergy of MIT and Cambridge working hand in hand.” When it comes to the local community, he knows that trust must be earned, not simply expected: “I want [school leaders] to know me and to know that when I come to them with something, that I mean it truthfully… that I’ve vetted this, that my background as an educator and a scientist means that I’m not just throwing things at you. That if I’m bringing something to you that means it has merit or that I think that it has merit, and I would like your input for it.”

When asked what is the one thing he wants the MIT community to know about him, Kundargi pauses for what feels like a long time—a silence that is particularly noticeable in its contrast to his usual volubility. It’s clear that he feels a lot of weight attached to what he’s going to say next and he wants to word his message carefully. “That I am a willing collaborator,” he offers at last, “I want to see what’s best for the people we work with, and I want to provide as many high-quality opportunities as possible for those who don’t have access to them.” And rest assured, if you’ve got input, he wants to hear from you: “I don’t care if it’s a thought you had, one talk you gave, if you’re someone who’s interested in K-12 education in any capacity within MIT, I want to know who you are, I want to talk to you, get a sense for what you’re interested in, because you never know when that one connection a year down the line might be useful.”

For Kundargi, everything comes down to relationships: the trust, and most of all, the commitment of everyone in the community. “People say they want to do something great and huge—more often than not, great and huge change happens when people are working together towards a common goal, are willing to collaborate. Those things don’t make the headlines of The New York Times, you’re not getting the 30 Under 30 Award for that, but that’s what makes systemic change. It just isn’t flashy, it isn’t sexy, it isn’t—whatever, but if you actually want to make a difference, that’s how you do it.”

Updated 08/27/2019

Comments are closed.